DD FINAL

2019

REFERENCES

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Breastplate of the Statue

Augustus of Prima Porta

Augustus of Prima Porta

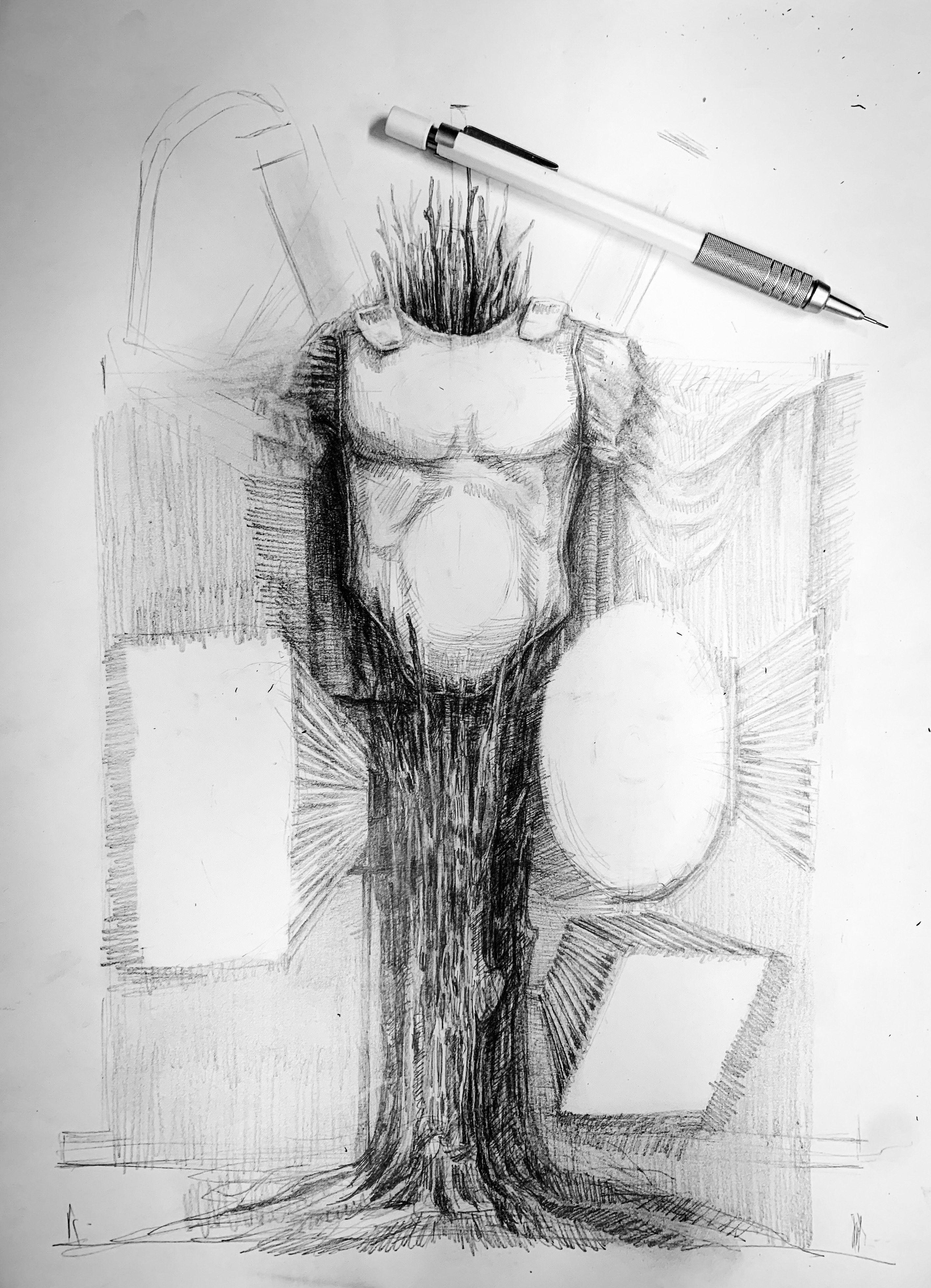

This figure is a Roman trophy (tropaeum). It is not a human figure, but it is an armored body with a helmet and breastplate that is put together on a tall pike to give off the semblance of a man. The armor is supposed to come from that of a defeated enemy. A similar trophy image, which includes the shields of defeated enemy soldiers, is located within a frieze from at the Temple of Apollo in Circo (Capitoline Museums).

This engraving by an unknown artist from the mid 16th century shows a Roman trophy. The first military trophies consisted of the arms and armour of the conquered hung from a tree. Transformed into stone sculptures by the Romans, they survived to be recorded by 16th century print makers and to inspire designers. This trophy is thought to commemorate the victory of the Roman General, Gaius Marius, over the tribe of the Cimbri, in 102 BC. This trophy is typical in its decoration: shields, swords, helmets and other weapons accompany the angels, centaurs, sphinx, flower decoration and tritons (or mermen).

The significance of the monument is a ritualistic notification of "victory" to the defeated enemies. Since warfare in the Greek world was largely a ritualistic affair in the archaic hoplite-age (see Hanson, The Western Way of War for further elaboration of this idea), the monument is used to reinforce the symbolic capital of the victory in the Greek community.

Ancient sources attest to the great deal of significance that early Greek cities placed upon symbols and ritual as linked to warfare – the story involving the bones of Orestes, for example, in Herodotus which go beyond the ritualistic properties to even magically 'guaranteeing' the Spartan victory, displays the same sort of interest in objects and symbols of power as they relate to military success or failure.

The trophies in Rome, on the other hand, would probably not be set up on the battle-site itself, but rather displayed prominently in the city of Rome. Romans were less concerned about impressing foreign powers or military rivals than they were in using military success to further their own political careers inside the city, especially during the later years of the Republic. A trophy displayed on the battlefield does not win votes, but one brought back and displayed as part of a triumph can impress the citizens (who might then vote in future elections in favor of the conqueror) or the nobles (with whom most aristocratic Romans of the Republican period were in a constant struggle for prestige).

The symbolism of the trophy became so well known that in later eras, Romans began to simply display images of them upon sculpted reliefs (see image and Tropaeum Traiani), to leave a permanent trace of the victory in question rather than the temporary monument of the trophy itself.

The significance of the monument is a ritualistic notification of "victory" to the defeated enemies. Since warfare in the Greek world was largely a ritualistic affair in the archaic hoplite-age (see Hanson, The Western Way of War for further elaboration of this idea), the monument is used to reinforce the symbolic capital of the victory in the Greek community.

Ancient sources attest to the great deal of significance that early Greek cities placed upon symbols and ritual as linked to warfare – the story involving the bones of Orestes, for example, in Herodotus which go beyond the ritualistic properties to even magically 'guaranteeing' the Spartan victory, displays the same sort of interest in objects and symbols of power as they relate to military success or failure.

The trophies in Rome, on the other hand, would probably not be set up on the battle-site itself, but rather displayed prominently in the city of Rome. Romans were less concerned about impressing foreign powers or military rivals than they were in using military success to further their own political careers inside the city, especially during the later years of the Republic. A trophy displayed on the battlefield does not win votes, but one brought back and displayed as part of a triumph can impress the citizens (who might then vote in future elections in favor of the conqueror) or the nobles (with whom most aristocratic Romans of the Republican period were in a constant struggle for prestige).

The symbolism of the trophy became so well known that in later eras, Romans began to simply display images of them upon sculpted reliefs (see image and Tropaeum Traiani), to leave a permanent trace of the victory in question rather than the temporary monument of the trophy itself.

A Marble Torso of an Emperor, Roman Imperial, Julio-Claudian, 1st half of the 1st Century A.D.

probably representing Augustus, Tiberius, or Claudius, carved in two parts, standing with the weight on his right leg and wearing a tunic, leather corselet with fringed lappets falling at the waist and shoulders, bronze cuirass, and paludamentum falling from the left shoulder over the back and formerly over the extended left forearm, the bronze breastplate decorated in relief on the chest with the god Sol emerging from the waters in a frontal quadriga and on the abdomen with two Victories flanking a trophy and hanging shields onto it, a large inverted palmette below with scrolling acanthus and rosettes on either side, the upper row of pteryges decorated with alternating feline heads above lotus flowers and addorsed rams' heads above palmettes, the lower row with alternating gorgoneia and palmettes, a bearded head interrupting the sequence on the right hip, the neck carved out for insertion of a portrait head.

probably representing Augustus, Tiberius, or Claudius, carved in two parts, standing with the weight on his right leg and wearing a tunic, leather corselet with fringed lappets falling at the waist and shoulders, bronze cuirass, and paludamentum falling from the left shoulder over the back and formerly over the extended left forearm, the bronze breastplate decorated in relief on the chest with the god Sol emerging from the waters in a frontal quadriga and on the abdomen with two Victories flanking a trophy and hanging shields onto it, a large inverted palmette below with scrolling acanthus and rosettes on either side, the upper row of pteryges decorated with alternating feline heads above lotus flowers and addorsed rams' heads above palmettes, the lower row with alternating gorgoneia and palmettes, a bearded head interrupting the sequence on the right hip, the neck carved out for insertion of a portrait head.

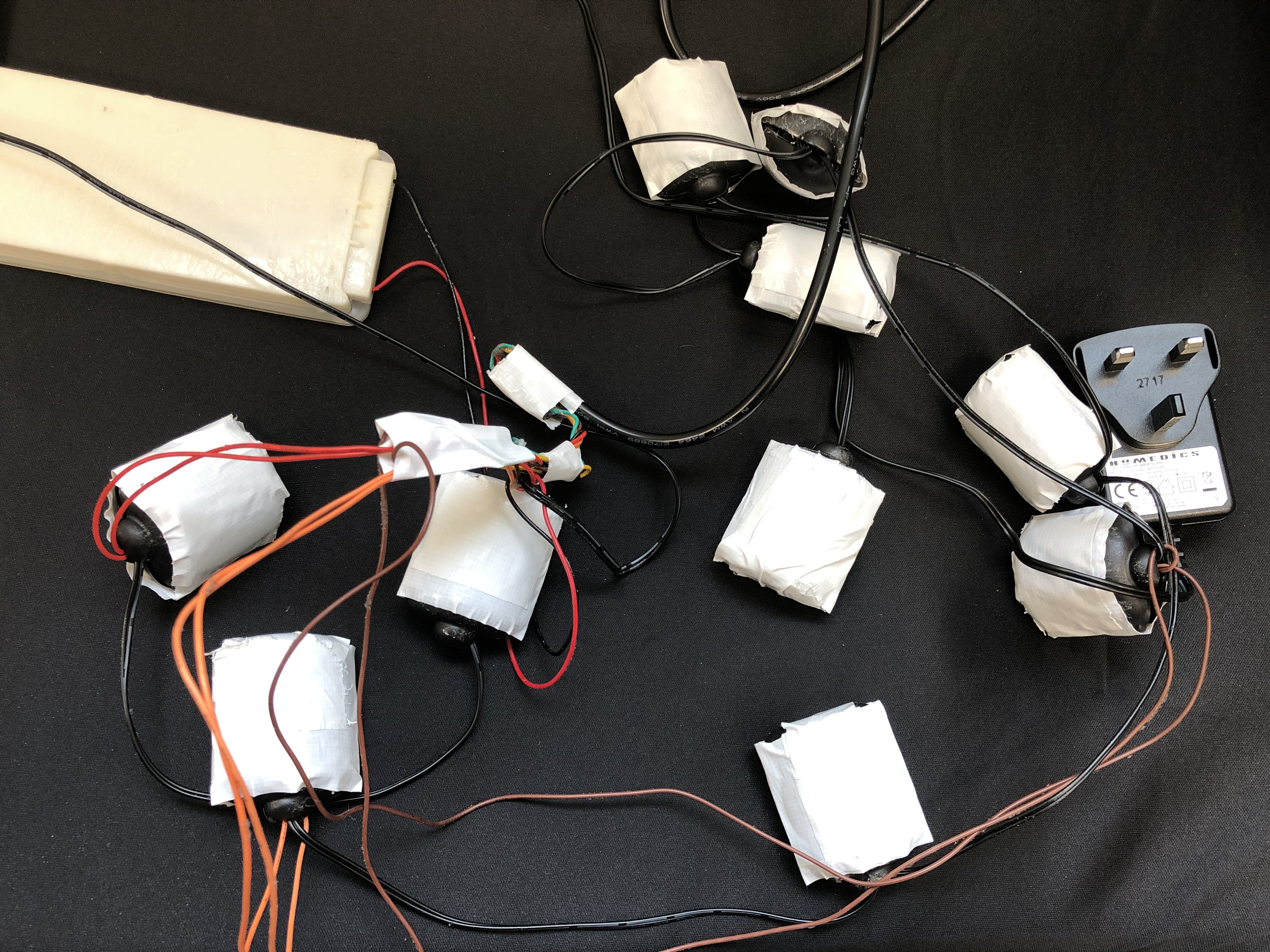

MAKING

Modeling